The Weeds Are Winning - But One Young Man Is Fighting Back

How a local ecologist is rallying a movement to save native ecosystems from invasive plants - one root at a time.

Need help with your yard? Get your free quote today!

Get a Free Quote! On a spring afternoon in British Columbia, a young man crouches under a tangle of blackberry brambles, his gloved hands yanking stubborn roots from the soil. The air is rich with birdsong and pollen, the ground thick with thorns and vines. It’s backbreaking work. It’s also urgent. The plants he’s pulling aren’t just garden nuisances. They’re ecological invaders, part of a quiet but relentless war being waged across the planet.

On a spring afternoon in British Columbia, a young man crouches under a tangle of blackberry brambles, his gloved hands yanking stubborn roots from the soil. The air is rich with birdsong and pollen, the ground thick with thorns and vines. It’s backbreaking work. It’s also urgent. The plants he’s pulling aren’t just garden nuisances. They’re ecological invaders, part of a quiet but relentless war being waged across the planet.

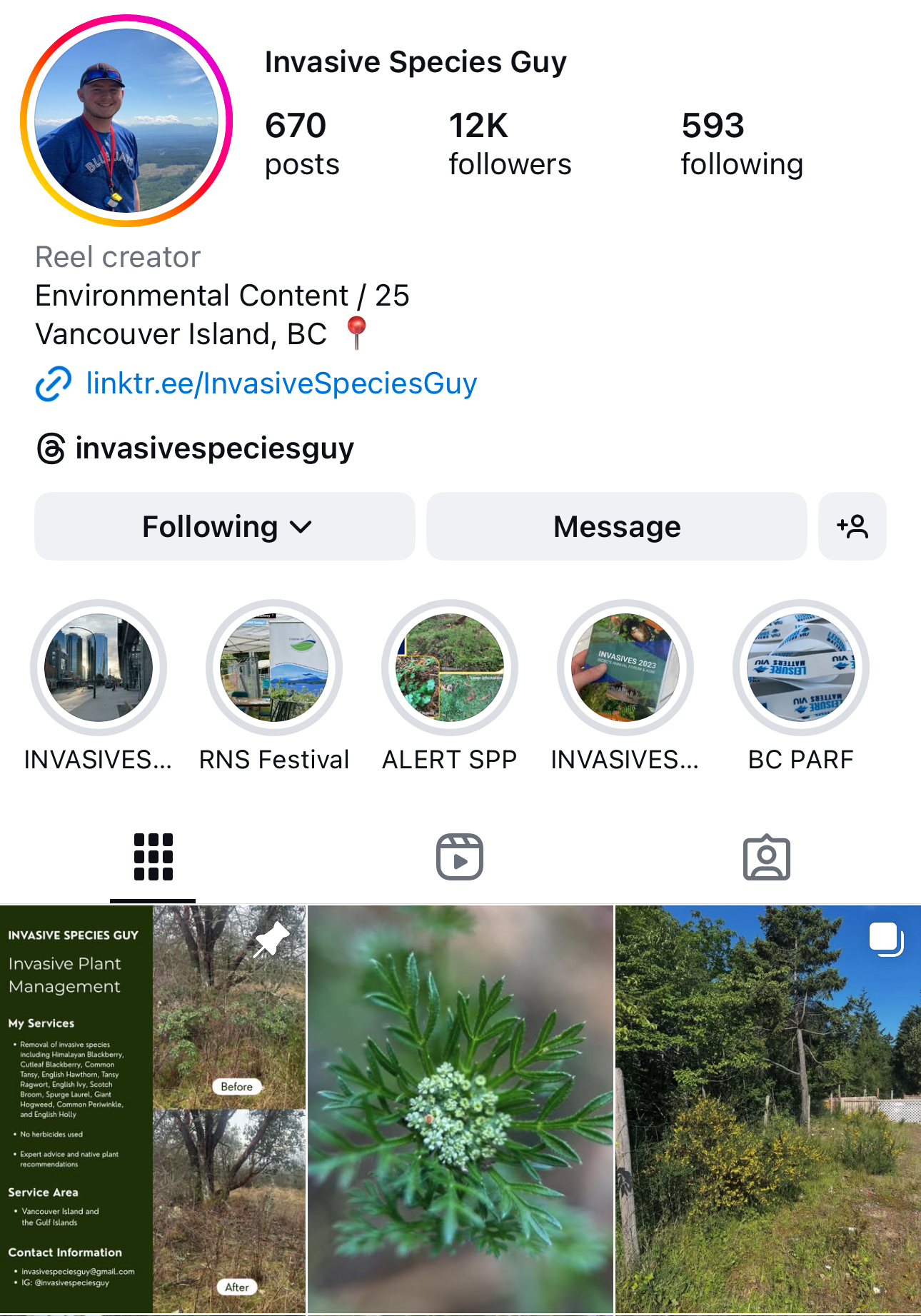

His name is Hunter Jarratt. Online, he goes by The Invasive Species Guy. And whether you know it or not, he’s fighting on your behalf.

Jarratt is part of a small but growing movement of ecologists, volunteers, and concerned citizens who are sounding the alarm about one of the most overlooked environmental threats of our time: invasive plants. These are the seemingly harmless flowers, vines, and shrubs that hitchhiked into North America from other continents and now overrun parks, forests, wetlands, and front yards - slowly but surely replacing native vegetation, degrading habitats, and altering the ecosystems that local wildlife depends on.

They’re hard to see. Harder to stop. And unlike wildfires or floods, they rarely make the evening news.

But the damage is profound. Invasive species are now one of the leading causes of global biodiversity loss. And with our world more connected than ever, the problem is accelerating. Ornamental plants from Asia, Africa, and Europe - often still sold in North American garden centers - are escaping cultivation and creeping across landscapes. Some, like English ivy and Scotch broom, were introduced over a century ago. Others are arriving now, quietly slipping through ports, nurseries, and backyard borders.

The Pacific Northwest, where Jarratt lives and works, is a cautionary tale. Native Garry oak ecosystems - once rich with wildflowers, butterflies, and birdsong - have been reduced to fragments, smothered by ivy, blackberry, and periwinkle. Coastal marshes are choked by yellow flag iris. Forest understories vanish beneath a carpet of Himalayan blackberry. Each plant displaces others, reshaping the entire food web. The result is a slow, steady unraveling of life as we know it - an ecological simplification with irreversible consequences.

Jarratt saw it happening and decided to do something. But he didn’t just pull weeds. He pulled back the veil.

Through a smartphone and a sense of mission, he began documenting invasive species in his community: how to identify them, why they’re harmful, and what people can do. His videos - equal parts fieldwork, science, and storytelling - now reach millions. He’s become a kind of guerrilla ecologist with a TikTok account, exposing the quiet damage hiding in plain sight. In one viral post, he visited local garden centers and revealed just how many invasive plants were still being sold. He showed mislabeled ivy, seed mixes filled with weedy intruders, and exotic flowers with beautiful blooms and destructive consequences.

The comments rolled in: “I had no idea.” “I planted that in my yard.” “What can I do?”

This is how change begins. Not with a legislative overhaul, but with a flicker of recognition. A shift in awareness. A domino falling.

The fight against invasive species won’t be won in a day. It’s complex, deeply rooted (literally and figuratively), and requires long-term commitment. But it can be won - if enough people care, if enough people act, and if we begin to recognize the front-line work that people like Jarratt are doing.

Because here’s the truth: our environmental priorities are misaligned. We celebrate tree planting, but ignore the invasive vine strangling it. We talk about pollinators, but let the flowers they need be buried under imported groundcover. We fund climate resilience while neglecting the habitat collapse happening beneath our feet. Invasive species work is underfunded, underpublicized, and underappreciated - precisely because it lacks drama. It’s not sexy. It’s slow. But it’s one of the most critical tasks of our time.

We need more invasive species guys. And girls. And gardeners. And scientists. We need school programs that teach native plant ecology. We need cities that rip out invasive hedges and replace them with habitat. We need governments to regulate plant imports and ban the sale of known ecological threats. And yes, we need social media - not just to entertain, but to educate and mobilize.

This isn’t about nostalgia or aesthetics. It’s about survival. Our ecosystems are finely tuned machines, the product of millions of years of co-evolution. When we replace native plants with imported species - even beautiful ones - we break those connections. Birds lose nesting grounds. Bees lose food. Amphibians lose shade. In time, we lose them too.

Jarratt isn’t waiting for someone else to fix it. He’s out there, restoring ecosystems one weed at a time. And by filming his efforts, sharing what he learns, and inviting others to join, he’s doing what our environmental institutions have failed to do: make the problem visible. Make it human. Make it matter.

We should listen. We should follow. We should fund this work.

Because invasive species aren’t just a nuisance - they’re a symptom of disconnection. And people like Hunter Jarratt are reconnecting us, root by root.